When will molecular electronics make the connection?

Computer chips based on single molecules may remain a work in progress, finds James Mitchell Crow but the technologies developed along the way are being used by chemists to explore their reactions

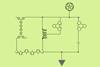

Squeezing down the size of electronic components to extract more performance from each new generation of gadget is a trend as old as the electronics industry itself. So perhaps it should be unsurprising that the concept of molecular-scale circuitry – as the ultimate expression of electronics miniaturisation – dates right back to the post-war period. Molecular electronics was arguably born with a 1974 theoretical paper published by Mark Ratner, a theoretical chemist at New York University in the US, and IBM synthetic chemist Ari Aviram. The pair proposed a specific polar organic molecule that could play the functional role of an electronic component called a rectifier.

At the time – aside from the synthetic challenge of making the proposed molecule – multiple technological barriers prevented the concept from being put into practice. There was no way to incorporate an individual molecule into a functioning circuit, let along connect the millions or billions of these molecules that would be needed on a chip. Almost half a century on, major progress has been made toward overcoming the technological barriers.