Cubanes help drugs take the strain

Medicinal chemists are increasingly exploring strained ring systems, George Barsted reports, believing they can serve as replacements for conventional building blocks in pharmaceuticals

Isosteres were first defined in the 1930s by Hans Erlenmeyer as ‘atoms, molecules or ions with identical peripheral electron distributions’. In 1951, Harris Friedman coined the term ’bioisostere’ to describe molecules conforming to the broadest isosteric definition while retaining similar biological activity. The hunt for bioisosteres meant that scientists could uncover building blocks that overcame problems such as solubility but still maintained the same potency for biological activity. Traditionally this could have been swapping a fluorine for a hydrogen on a compound, or changing a benzene to a pyridine.

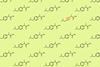

Following Philip Eaton’s proposition of cubane as a substitute for benzene, it took nearly two decades for chemists to begin implementing his concepts. Cubane and other strained molecules had made sporadic appearances in literature for medicinal chemists but were largely seen as weird compounds that represented a challenge for synthetic chemists, with a lack of application for biological activity.