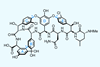

(+)-Vancomycin aglycon

Optimising for efficiency deserves credit too

Society doesn’t give enough credit for incremental improvement. It’s not common knowledge who got to the top of Everest the fastest, or who got into space the cheapest – people remember who was first. The field of total synthesis is similar, and I’ve written before about how the most memorable syntheses of a particular target are the first – or sometimes the last (ie the best).

The problem is that even these ‘best’ syntheses are rarely optimised for efficiency or practicality. In this context, we tend to award this moniker to the cleverest, quirkiest or most elegant way of making a molecule – often the kind of routes you’d love to read about but hate to go and execute. Most often, the chemists behind these approaches will have only tried to optimise one or two key steps, letting everything else largely fall where it may. There’s no extra credit for getting 95% instead of 70% on that Swern oxidation that most readers will skim over, so why try?